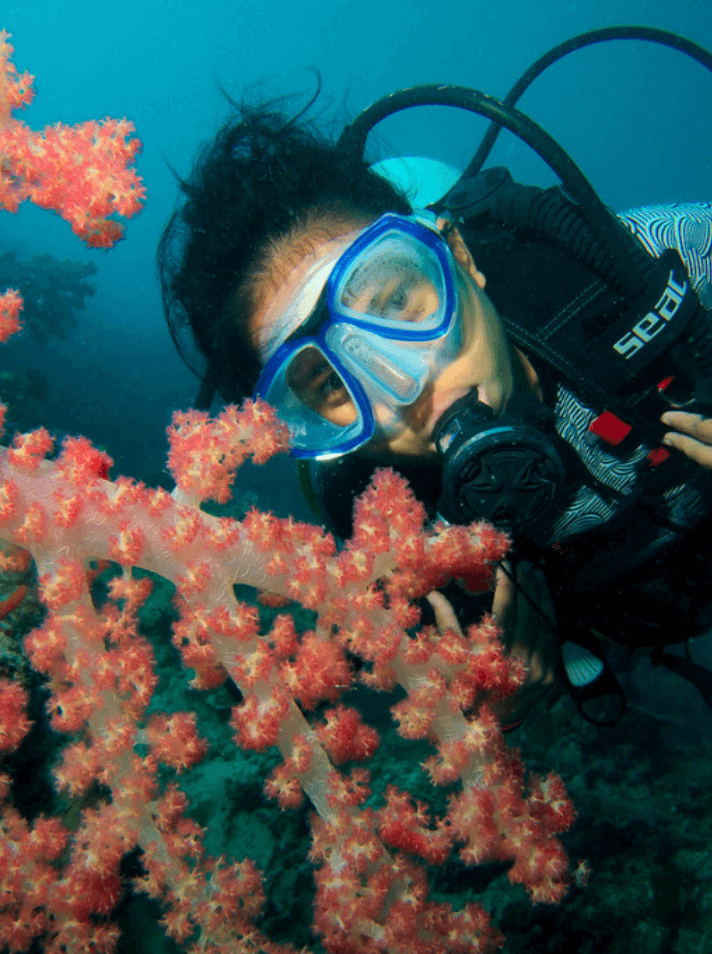

I wrote a few blog posts ago about the steps a nascent scuba diver should take to be fit enough for the Open Water Diver course. These tips will give you the very basics to be fit enough to learn to dive. After these initial steps, you will likely be hooked on diving, and dive a lot. Especially in this case, you’ll want to stay fit and become fitter. Scuba diving itself can be draining due to the time spent in the water causing heat loss, due to breathing hyperbaric air, and due to breathing rather dry tank air. So you have to be fit for diving, but it will not usually get you in shape. I also wrote about creative scuba fitness ideas for divers in remote locations sans gym.

Today I’ll talk about combining training and diving; These tips are meant for the busy diver; either someone on an extended dive trip, a dive pro who spends his or her life diving during most days, or a scientist doing intensive fieldwork underwater. How do you combine a lot of time spent diving with quality, intense exercise?

Training First, Diving Second

The matter of how exercise and training should be times is complex. There is evidence that exercise after scuba diving is detrimental to your health; the likelihood of decompression illness (DCI) increases. Powell in “Deco for Divers” states that:

During the decompression phase of the dive and immediately after surfacing excessive exercise should be avoided as this can significantly increase the risk of bubble formation.

It makes sense – mechanical stress on the micro-scale, as experienced during exercise, will lead to forces that will form bubbles from excess dissolved nitrogen. The effect is not unlike the bubbles bubbling out of a soft drink can when shaking it. I am waving my hands here a bit, but this is the most likely candidate for a mechanism why exercise post-dive – when the body is loaded with excess nitrogen – is a bad idea.

There is also evidence that exercise before diving is good – it can reduce your likelihood of DCI. This is likely due to an increased blood flow through your tissues post-exercise – bubbles will be removed more effectively. An example of a study showing this is the study by Castagna and colleagues (2010, see the references below). Divers were running on a treadmill for 45 min an hour before a dive. This significantly reduces “bubble grades”, a score of bubbles measured in the bloodstreams of the subjects with a Doppler radar.

I have trained after dives, on the same day. Common sense goes a long way here. These were shallow (< 20 meters), non-decompression dives in warm water. I waited several hours and then went to lift weights, less intense than usual. My body is well used to diving and lifting. Follow my example at your own risk! Generally, a pre-dive workout is preferred.

Intense and Short

This, in contrast to tip number one, is a somewhat subjective take of mine. It works for me.

I am not excluding that for others, a 90+ minute run or bike in the early morning is the right kind of exercise. For me, the shorter time spent on a brief, intense workout makes it easier to fit it into a busy day with two or more dives. A shorter session drains me less mentally. It will also generally lead to less dehydration (see below).

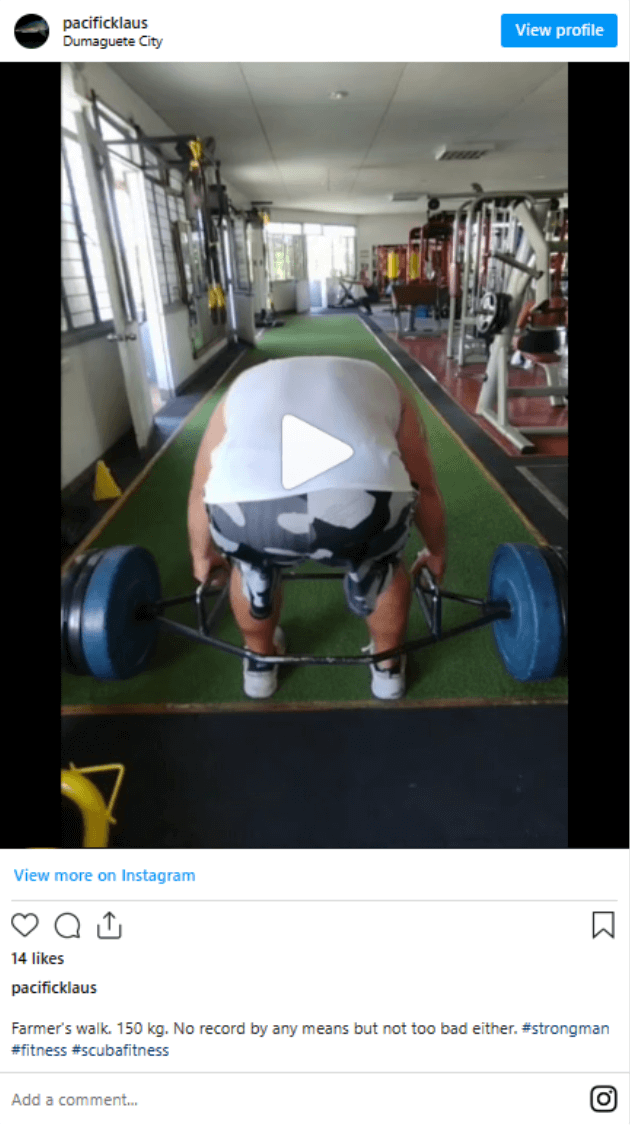

What I like to do is an intense strength-training session. I focus on complex whole-body movements like squats, deadlifts, benches, or overhead presses. Alternatively, I do strongman exercises, like the farmers’ walk shown below:

Rehydrate

This point is crucial. A lot of diving happens in warmer, or hot climates. The air in scuba tanks is dry, a consequence of how it is compressed into these tanks. You have probably experienced a really dry mouth during a long dive – the typical sign of dry tank air. So, the warm climate, the dry scuba tank air, possible caffeine consumption (a dehydrating agent – I’m guilty of over-indulging!) and the sweat lost when exercising all add up to the danger of serious dehydration.

Dehydration is detrimental to athletic performance in all contexts, but it’s particularly bad during scuba diving. Two effects stand out: The increased likelihood of DCI when dehydrated, and the danger of cramps.

Dehydration leads to an increased propensity for DCI since it causes the blood vessels to restrict when the body does not have enough liquid in it; the bubbles formed in your bloodstream can get stuck more easily in these narrower capillaries, and this causes DCI.

A study by Fahlman and Dromsky (2006, see below) tested the relationship between DCI and dehydration in pigs that were sent on a “dive” in a decompression chamber. Half of the pigs could drink as much as they wanted to, the other half got no water, and a (dehydrating) diuretic drug. The second group had significantly more cases of DCI and death from DCI. This is the kind of experiment that you definitely can’t do with humans! Fahlman and Dromsky’s conclusion was that dehydration significantly increased the overall risk of severe DCS and death. The pig results generalize to humans (we are mammals of a similar size).

Dehydration also leads to a risk for cramps, which can be very unpleasant, and lead to downstream problems (can’t catch up with a dive buddy).

Hence: Drink! Make sure to remember to bring a drink bottle, or check if there is water on the boat. Make a habit of taking a big drink just before jumping in the water; this is easily forgotten in the positive, but sometimes hectic pre-dive excitement. Also, I like to drink mineral drinks; simply drinking water will lead to mineral depletion. In the Philippines I get “Berocca”, mineral tablets that quickly dissolve in water and add vitamins and Magnesium; there are many similar products available. Ready-made sports drinks often contain a lot of sugar; It’s a viable option to dilute these with water, at least 1:1.

I hope these tips are useful, they come from my experiences, and I do think that they are more specific than the usual “stay fit to dive!”,

Best Fishes,

Klaus